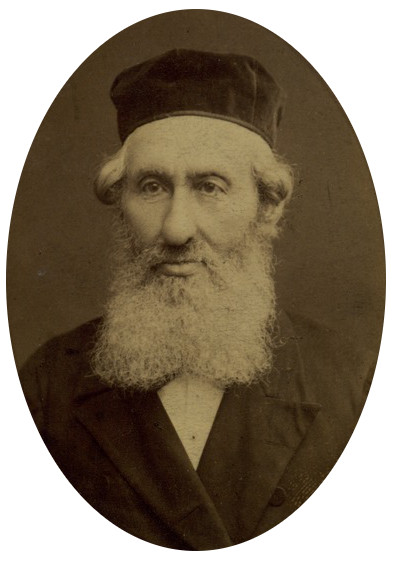

Kalman Schulman who lived and worked in Vilna (Vilnius), Lithuania, was an important agent of culture in his time and a prominent member of the Jewish Enlightenment movement in Eastern Europe, but was later almost totally forgotten and neglected. The appearance in the mid-nineteenth century of his translations of Josephus, made from Paret’s German, were a highly significant event in the history of Jewish culture. For generations, Josephus’s works had been absent from the Jewish library, and the collective memory drew mainly upon talmudic sources and the Book of Yosippon. In 1861 Schulman published an open letter in the new Hebrew periodical, Hakarmel, printed by his close friend Shmuel Yosef Fünn, to sign up advance subscribers. He explained that it was inconceivable that the masterpiece of ‘the noblest of all the writers of antiquities in our generations and the finest of all authors of ancient history’, which has already been translated ‘into all the languages on the earth’, has never appeared in Hebrew. The first volume in this well-planned project was Toledot Yosef (‘The Life of Josephus’) in 1859, followed by a biographical article in the periodical Hakarmel (1860). The two parts of Wars of the Jews, comprising close to 800 pages, appeared in 1862, followed by an abridgement of Josephus’s Antiquities, beginning with the reign of Cyrus and concluding with Herod the Great.

Kalman Schulman who lived and worked in Vilna (Vilnius), Lithuania, was an important agent of culture in his time and a prominent member of the Jewish Enlightenment movement in Eastern Europe, but was later almost totally forgotten and neglected. The appearance in the mid-nineteenth century of his translations of Josephus, made from Paret’s German, were a highly significant event in the history of Jewish culture. For generations, Josephus’s works had been absent from the Jewish library, and the collective memory drew mainly upon talmudic sources and the Book of Yosippon. In 1861 Schulman published an open letter in the new Hebrew periodical, Hakarmel, printed by his close friend Shmuel Yosef Fünn, to sign up advance subscribers. He explained that it was inconceivable that the masterpiece of ‘the noblest of all the writers of antiquities in our generations and the finest of all authors of ancient history’, which has already been translated ‘into all the languages on the earth’, has never appeared in Hebrew. The first volume in this well-planned project was Toledot Yosef (‘The Life of Josephus’) in 1859, followed by a biographical article in the periodical Hakarmel (1860). The two parts of Wars of the Jews, comprising close to 800 pages, appeared in 1862, followed by an abridgement of Josephus’s Antiquities, beginning with the reign of Cyrus and concluding with Herod the Great.

Schulman’s translation read like a dramatic historical novel depicting the rich political events of the last years of Jewish independence and culminating in the battles between the rebels and the Romans and in the destruction of the Temple. Beyond his literary ambition to make forgotten literature available, the translation of Josephus’s Jewish War was intended by Schulman to strengthen Jewish national identity by reconnecting it to ancient history, part of an endeavour to redeem what remained from a glorious era lived in the Land of Israel. Schulman’s wider goal was to engender a revolution in the Jewish book world by expanding it into two hitherto neglected spheres, geography and history.

Schulman offered an alternative to the hostility to, and defamation of, Josephus that he found in German-Jewish historiography, and refused to denounce him as a traitor. His extremely sympathetic attitude reflects also the ideology of the moderate Haskalah in advocating Russian patriotism, complete loyalty to the government, and identification with the Russian empire and its Jewish policy. He unreservedly accepted the pacific position of his hero. His clearly negative view of the revolt against the Romans was often repeated in his writings. In his eyes, the Zealots were responsible for the destruction of the Temple. The political revolt was totally devoid of any legitimacy, for ‘he who rebels against his king also rebels against God who has enthroned him’.

Schulman’s translations contributed to the secularization of Jewish culture, even though today we would consider him an orthodox Jew. Like the other moderate maskilim in Vilna, Schulman greatly admired the Gaon of Vilna, and the approbation he received for his Wars of the Jews from Rabbi Abraham Simha of Mastislav granted legitimacy to the translation project. Schulman is depicted as fulfilling the Gaon’s wish, passed on, according to the Lithuanian tradition, from the Gaon to Rabbi Baruch of Shklov, to have books of science translated into Hebrew, explicitly including the writings of Josephus, serving as an aid to the study of the Talmud.

Schulman, Kalman, Toledot Yosef (‘The Life of Josephus’). Vilna, 1859.

Schulman, Kalman, Milkhamot Ha-Yehudim ‘Im Ha-Romaim (‘The War of the Jews against the Romans’). Vilna, 1862.

Schulman, Kalan, Kadmoniot Ha-Yehudim (‘Antiquities of the Jews’). Vilna, 1864.

Feiner, S., Haskalah and History: The Emergence of a Modern Jewish Historical Consciousness. Oxford, 2002: 247-53.

Kahn, L., ‘Kalman Schulman’s Hebrew Translation of Josephus’s Jewish War’, in Josephus in Modern Jewish Culture: New Perspectives, ed. A. Schatz, forthcoming.

JRA entry contributed by Shmuel Feiner